Though many see the church as a place of healing and sanctuary, the truth is far more complex. Truth be told, often times, the church is the worst place for women to go to seek support when they have been sexually assaulted – and many, many women are working hard to change this. The Rev. Dr. Leslie D. Callahan will be reflecting on this very reality as we begin the second week of Women’s History Month, and we know you’ll find her reflection insightful. Read, comment, and share.

Rev. Dr. Linda E. Thomas – Professor of Theology and Anthropology, Chair of LSTC’s Diversity Committee, Editor – “We Talk. We Listen.”

We were in a circle when we told our stories. It was an impromptu gathering of women, most of us clergy. Earlier we had all participated either as performers or audience during an evening of spoken word and music. And we were filled both from the poetry and from dinner. Into the wee hours, we told our stories. Woman after woman. Violation after violation. Stories of assault by next door neighbors and cousins, in our own homes and on public transportation. Experiences of broken bodies and broken trust. And as the stories poured out, I felt despair.

The sense of despair startled me. I was a new pastor then, energized by a greater sense of hope and possibility than I had ever known before. Anything and everything seemed possible. An established Baptist church had taken the leap and done something different: they elected a single woman to head their 120-year-old church. They were receptive to my leadership.

The world was changing. But not fast enough.

Not fast enough to heal the brokenness in the eyes of my sisters.

Not fast enough to restore the sense of safety a girl in my own church had lost when she was molested in our basement.

What shook me that evening was the sense that We cannot keep our daughters safe.

I recognized just how ineffective the church is, how disconnected from the substantial need of the women who make up the bulk of our congregations and who live with the aftermath of violation.

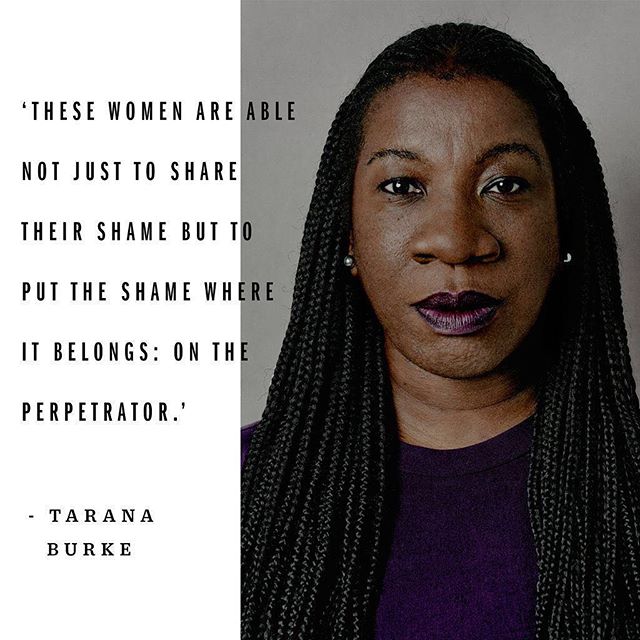

Tarana Burke began the #MeToo movement to turn the realization of the ubiquity of sexual violence against Black girls and women from a source of despair to an opportunity for camaraderie and change. Rather than taking the fact that so many women can say “me too” as a sign of the intractability of the problem of harassment and assault, Burke understood a decade ago what women around the nation are coming to clarity about now, that there is healing and power in bringing the truth to light in community—healing and power not only for the women who speak together but also transformative power to change the environment in which we all live.

Although the work is just beginning, there are signs that the culture is shifting to take seriously the harm that has been done. Boardrooms and studio sets will be different because of the courage women have had in telling the stories of harassment and assault.

The question is what will happen in and to the church when the reckoning comes.

Frankly, the church is overdue for its #MeToo moment. Congregations and denominations, seminaries and parachurch organizations all are implicated in the pervasiveness of sexual assault and harassment. Too often the church is the prime location for attitudes that protect perpetrators to the continual harm of their victims.

After the conviction of serial predator Dr. Larry Nasser, Rachael Denhollander, the first woman to publicly accuse him, talked in Christianity Today about the toll that standing with victims took on her relationship with her own church by noting that “church is one of the worst places to go for help.”[1] The reasons for the lack of responsiveness are many, but at the heart of the problem is a theological one, that is, the failure to regard the well-being and dignity of women and girls as central to the message of abundant life that Jesus Christ proclaimed and promised.

photo illustration by Kathleen Barry, UMNS

As a participant in the progressive side of the Black Church, I am specifically concerned that we attend to this and get it right as a feature of our understanding of justice work. Too often we have been guilty of limiting the church’s justice labor simply in terms of its advocacy for racial justice narrowly defined. This tension became obvious after the Golden Globe awards when entertainment leaders invited women who work for activist organizations to join them on the red carpet to highlight the relationship between sexual violence and economic status.

Accepting an award for lifetime achievement, Oprah Winfrey, herself a sexual assault survivor, gave an epic address that made the connection between sexual violence, economic vulnerability, and racism explicit especially by invoking the memory of Recy Taylor, who was gang raped in 1944 by six white men while walking home from church.

Especially on social media, several Black preachers decried this association as somehow diminishing the horror of what Mrs. Taylor suffered at the hands of the white men who raped her.

Recy Taylor, after touring the White House in 2011.

While all of us acknowledge that sexual harassment and sexual assault are not identical experiences—indeed that all kinds of abuse exist on a continuum—the refusal to recognize that sexual harassment is a form of abuse inhibits our capacity to proclaim a consistent justice message.

Rather than dismissing the capacity of rich white women to be abused, what we ought to proclaim is the insight of intersectionality, that is, that race and class intensify and exacerbate vulnerability to harm and violence. If privileged white women are silenced, then marginalized and poor women of color are only more so.

I fear that we have been slow to bring this to light because we know that some of our favorites will be exposed when the reckoning comes. Our churches too long have been harems for charismatic leaders. There are too many stories of revivalists being provided company for their week away from home, too many allowances for the bad behavior of great preachers. But just as the worlds of art and film have had to face that the actions of the creative perpetrators of harassment and assault are inexcusable, it’s now our turn.

We know that actors and writers and scholars and other creative women have left their fields after they have been harassed and assaulted by powerful persons in those fields.

We now need to wonder how many gifts in the church have been stifled because women have been treated as objects. How many great preachers have we lost because women whose gifts should have been nurtured were sacrificed to the great orators we had?

It’s our turn.

The conversation with my sisters years ago shaped my pastorate. It posed the question I feel compelled to answer in my preaching and pastoral care work: How do we keep our people safe? In the years since, I have heard many more stories, not just from women and girls but also from men and boys, about the injuries their bodies and minds sustained from perpetrators but also about the injuries their spirits sustained because the church would not hear them. The good news is that we can change.

Believing that the life and ministry of Jesus sealed by his resurrection portend God’s new creation, we in the church can and must prioritize the healing of those who have been harmed by sexual violence and the transformation of the world such that that violence ceases.

The beginning of the work occurs when we make room for the stories of those who say “me too,” bearing witness to the love of the God who loves us and wills for us to be healed and whole.

[1] http://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2018/january-web-only/rachael-denhollander-larry-nassar-forgiveness-gospel.html

Source: We Talk. We Listen.

A native of Gary, West Virginia, Dr. Leslie D. Callahanexperienced her first Christian education and formation at Apostolic Temple Church where she developed an enduring love for Jesus Christ and for Christ’s body, the Church. Having experienced her call to ministry at an early age, Dr. Callahan began the public proclamation of the gospel at age 19. Committed to education, Dr. Callahan earned the Bachelor of Arts in Religion from Harvard University/Radcliffe, the Master of Divinity from Union Theological Seminary, and the Doctor of Philosophy degree in Religion from Princeton University. Her research interests include religious history in the United States, particularly independent African American Christianity and Pentecostal Studies. A gifted professor, Dr. Callahan, served on the faculty of New York Theological Seminary (NYTS) as Assistant Professor of Modern Church History and African American Studies. Prior to her time at NYTS, she was a member of the faculty of the University of Pennsylvania as assistant professor of religious studies. Dr. Callahan currently serves as a Commissioner for the Philadelphia Housing Authority. She is also an active member of the Philadelphia Alumnae Chapter of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc. In addition to her ministry and scholarly pursuits, Dr. Callahan enjoys traveling, golfing, reading, movies, and sports.

A native of Gary, West Virginia, Dr. Leslie D. Callahanexperienced her first Christian education and formation at Apostolic Temple Church where she developed an enduring love for Jesus Christ and for Christ’s body, the Church. Having experienced her call to ministry at an early age, Dr. Callahan began the public proclamation of the gospel at age 19. Committed to education, Dr. Callahan earned the Bachelor of Arts in Religion from Harvard University/Radcliffe, the Master of Divinity from Union Theological Seminary, and the Doctor of Philosophy degree in Religion from Princeton University. Her research interests include religious history in the United States, particularly independent African American Christianity and Pentecostal Studies. A gifted professor, Dr. Callahan, served on the faculty of New York Theological Seminary (NYTS) as Assistant Professor of Modern Church History and African American Studies. Prior to her time at NYTS, she was a member of the faculty of the University of Pennsylvania as assistant professor of religious studies. Dr. Callahan currently serves as a Commissioner for the Philadelphia Housing Authority. She is also an active member of the Philadelphia Alumnae Chapter of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc. In addition to her ministry and scholarly pursuits, Dr. Callahan enjoys traveling, golfing, reading, movies, and sports.

Facebook Comments