By Rev. Dr. Linda E. Thomas, We Talk. We Listen.

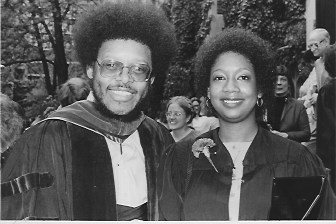

Me and Dr. Cone at my graduation from Union Theological Seminary.

It is hard to describe my relationship to the Rev. Dr. James H. Cone – it is hard for all of us who were marked by this great man. Yet, as someone who has carried his legacy, and who must carry this legacy even more boldly now that he has gone home, it is important for me to do what I can to share what this man has meant to me, and by extension, what he means to the Academy and the Church. May my offering be acceptable in your sights. Read, comment, and share.

Rev. Dr. Linda E. Thomas – Professor of Theology and Anthropology, Chair of LSTC’s Diversity Committee, Editor – “We Talk. We Listen.”

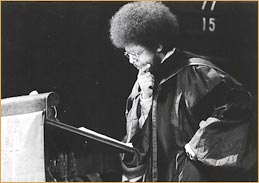

The Rev. Dr. James H. Cone in the late 60’s, early in his career.

On Saturday morning, 29 April 2018, I received a text from my BFF, Rev. Dr. Kelly Brown Douglas that our beloved mentor, Dr. James Hal Cone had died. Although I’d anticipated this communiqué, my mind could not fully grasp the feelings my body held. Like a dam that had burst, memories flooded my mind. My long-term memory bank released a tsunami of images flooding my entire being.

I was exhausted in just a few moments.

The grieving process had begun and moves to a new junction as the Life of Dr. James Hal Cone is celebrating at his “Home Going” Service today at 11 a.m. at the Riverside Church in New York City. I am attending that service with my daughter, Dora.

This week I dedicate this blog post to Dr. James H. Cone.

The announcement of his passing went around the world in a matter of seconds. My Facebook page showed messages in a variety of languages, some unrecognizable to me. Dr. James Cone did two basic things that reshaped theological discourse throughout the globe. First, he re-imagined the image of God, positing that God is Black. Second, his book Black Theology and Black Power published 1969 presented the first systematic presentation of Black Theology bringing to light God presence in the struggle for freedom by black Americans centered in the gospel message of salvation. Written in light of the commencement of the Civil Rights Movement this book thundered to the world a theological anthropology that Black Lives Matter.

There are so many ways to write this post.

I will take the path of simplicity so that as many people as possible, including children can know this iconic person..

Early Life, Faith Formation, and White Supremacy

James Cone was born in Fordyce, Arkansas in 1939 and grew up in the small town, Bearden. He lived with a diunital reality: the love and affirmation of the historic Black church realized through African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) he attended with his family and a normative death-dealing anti-black racism.

White culture of the south and elsewhere in the United States at that time actively displayed social norms that devalued Black people. Cone and his brother always stayed up late until they heard their father’s truck drive up, signaling that he was home from his day of work.

Cone’s mother comforted her sons by teaching them the power of God in history and in every present moment. She taught them that Jesus’ power was with them and that Jesus knew about suffering so he understood the plight of black people. She also taught that the Holy Spirit was actively present, giving them a kind of protection and freedom that transcended the worries of this world.

Their church taught them the same. And even though they were surrounded by dangers of white supremacy, and therefore always in danger, they were in God’s hands.

Education, Vocation, the persistence of racism and Cone’s Response

Cone went to Shorter College and Philander Smith College in Little Rock receiving his B.A. in 1958. Acknowledging his call to ordained ministry he entered divinity studies at Garrett Theological Seminary and graduated with a Bachelor of Divinity degree in 1961. He received his M.A. from Northwestern University in 1963, and his Ph.D. from the same institution in 1965.

There, too, he experienced racism.

Upon finding out that James Cone was black, his initial scholarship was reneged and he had to take on janitorial duties to support himself. Despite everything, though, he persevered. He told his white student colleagues that he would eventually write about the God Human relationship for the perspective of black people and they retorted that black people were not worthy of being reflected upon theologically, but just as his classmates at Garrett discounted his scholarship so did the white theological academy. Even so, Cone’s critiqued white theologians and the white church because he believed that to be the task of the theologian. His writing radically criticized one of the US’s most beloved theologians, Reinhold Niebuhr – whose theological imagination thrilled white culture while telling Black folks who lives were mired by structural racism to “go slow” as they pushed for equality during the Civil Rights Movement.

Anyone who knew James Cone knew that he cared very little about what white folks thought of him or his theological commitments. He focused his entire life on the theological relationship between God and Black people. Moreover, his focus was not on “when we all get to heaven” but rather on “Thy Kingdom come on earth …” His entire vocation endlessly proclaimed that the “Kin-dom” of God – as evinced in the lives of Black people – was indeed an integral and powerful vision of what the Church needed to be – this was very different from the white theology espoused by most white theologians and the majority of white churches.

Systematic Theological Response: Black Theology and Black Power (1969)

When the dreams and frustrations of Black People erupted in protest and resistance in the 1960’s, James Cone put pen to paper and wrote, Black Theology and Black Power, declaring that God was in the midst of these eruptions, making these protests and demonstrations “good.”

Moreover, since the God of Black people loved Black people as much as White people, and since that same God died on the Cross for Black people as God had for White People, then as baptized Christians Black people had no choice, but to love themselves as they loved their neighbors. This meant rising up to defend themselves when White Christians participated in the oppression of Black people.

For Cone, institutions entrapment of black citizens in cycles of poverty, poor education, discriminatory laws, and a church unrepentant for its open racism was the deep and insipid sin that the nation needed to confront.

But though white society and the white church would shout “Peace! Peace!” as dogs attacked beautifully, Sunday-church clad black folks and KKK members bombed churches and killed beautifully Sunday-church clad black children, people of African Descent across the nation shouted “There is no peace!”

Systematic Theological Response: The Cross and the Lynching Tree (2011)

In 2011, Cone’s final book, The Cross and the Lynching Tree was published. Hear his words:

“What is invisible to white Christians and their theologians is inescapable to black people. The Cross is a reminder that the world is fraught with many contradictions–many lynching trees. We cannot forget the terror of the lynching tree no matter how hard we try. It is buried deep in the living memory and psychology of the black experience in America. We can go to churches and celebrate our religious heritage, but the tragic memory of the black holocaust in America’s history is still waiting to find theological meaning. When black people sing about Jesus’ cross, they often think of black lives lost to the lynching tree …to the gun of white police” (Cone 2012: 159-160).

Cone resilience came from the teachings of his early faith community, his faith was matched by a deliberate Christian ethics grounded in the gospel of Jesus Christ for the salvation of humanity and as his scholarly record demonstrates he made consistent scholarly contributions throughout his life. These writing demonstrate his evolving self that adapted to encounters with interfaith traditions, black women’s and women of color’s articulation of sexism and gender discrimination in their cultural context, ecological theology, and much, much more.

His legacy includes nine books of which four have been translated into nine languages. He published over 150 articles; was granted numerous awards distinguished awards and lectured at myriad universities and public societies and institutes throughout the United States, Africa, Asia, the Caribbean, and Latin America.

The power of Cone’s work is that calls the Church to connect the it collusion with if not direct participation in the oppression of black people in America to the cross and the lynching tree thereby linking the execution of Jesus by the Roman State with the murder of black people by lynching whether by mob or by gun.

Moreover, the resurrection represents God’s love for the marginalized to create movements like the Civil Rights movement, and Black Lives Matter, #MeToo – to mark resistance against “populist” thrusts to “Make America Great Again.” The Church must be the “head light rather then the tail light.” Cone’s work calls the entire church to that which non-black leaders who are part of the culturally dominant group to recall the marks of the church and to re-member the church.

Perhaps, in this time and place, the church for a public church is what is the church going to choose to be? Who is the church going to serve?

And that is what we must continue to do, friends.

That is what we must continue to do – to preach to the Church, to all people, to pay heed to the marginalized voices within it so that it might “re-member” or become whole flesh again. Cone pointed a way forward back in 1969 when he published “Black Theology and Black Power,” as a reminder for the church in the United States to get back into it’s body, to deal with it’s pain and injustices. And if there is one thing that he taught so many of us over the years – students, mentees, readers, all of us – was that it is only when we use our distinct theological voices can we be sure that we speak the most clearly.

So in memory of my teacher, mentor, and friend – keep on speaking!

Dr. Linda E. Thomas has engaged students, scholars and communities as a scholar for thirty-one years. She studies, researches, writes, speaks and teaches about the intersection and mutual influence of culture and religion. Her work is rooted intransitively in a Womanist perspective. An ordained Methodist pastor for 35 years with a Ph.D. in Anthropology from The American University in Washington, D. C. and a Master of Divinity from Union Theological Seminary in New York City, Dr. Thomas’s work has taken her to South Africa, Peru, Cuba and Russia. She has been recognized as an Association of Theological Schools Faculty Fellow as well as a Pew Charitable Trust Scholar.

Dr. Linda E. Thomas has engaged students, scholars and communities as a scholar for thirty-one years. She studies, researches, writes, speaks and teaches about the intersection and mutual influence of culture and religion. Her work is rooted intransitively in a Womanist perspective. An ordained Methodist pastor for 35 years with a Ph.D. in Anthropology from The American University in Washington, D. C. and a Master of Divinity from Union Theological Seminary in New York City, Dr. Thomas’s work has taken her to South Africa, Peru, Cuba and Russia. She has been recognized as an Association of Theological Schools Faculty Fellow as well as a Pew Charitable Trust Scholar.

Facebook Comments